Anxiety: Our Step-by-Step Guide to Notice It, Feel It, and Move Through It

"Combatting Anxiety: A Proven Guide to Identifying and Managing Your Stress"

We remember the moment like a soundscape: a low hum of worry in the chest, a dry mouth, the air feeling a touch colder because our breath is shallow. That’s Anxiety — uninvited, insistent, and oddly persuasive. In this guide, inspired by our teaching and clinical experience with Therapy in a Nutshell (and yes, the practical work of Emma McAdam), we will walk through a clear, practical, five-step method to process Anxiety rather than merely survive it.

We want to be with you in this: we know what Anxiety smells like at 2 a.m., what it tastes like caffeine and stale popcorn, how it buzzes under the skin like an overexcited fly. We’ll show you how to observe it, how to choose willingness, how to explore what it’s telling us, how to clarify what is actionable, and finally how to act or accept. Along the way we’ll use three characters — Bob (social Anxiety), Jane (general Anxiety), and Fred (event Anxiety) — to show how the steps apply in real, sometimes messy life.

We’ll be honest: Anxiety is uncomfortable, sometimes unbearably so. But it’s not an enemy to annihilate. It’s a signal we can learn to read and respond to with intention. We’ll walk with you through the whole process, and by the end we hope you feel less like you’re being worn down by Anxiety and more like you’re learning its language.

What this guide covers — an outline of the five steps 🗺️

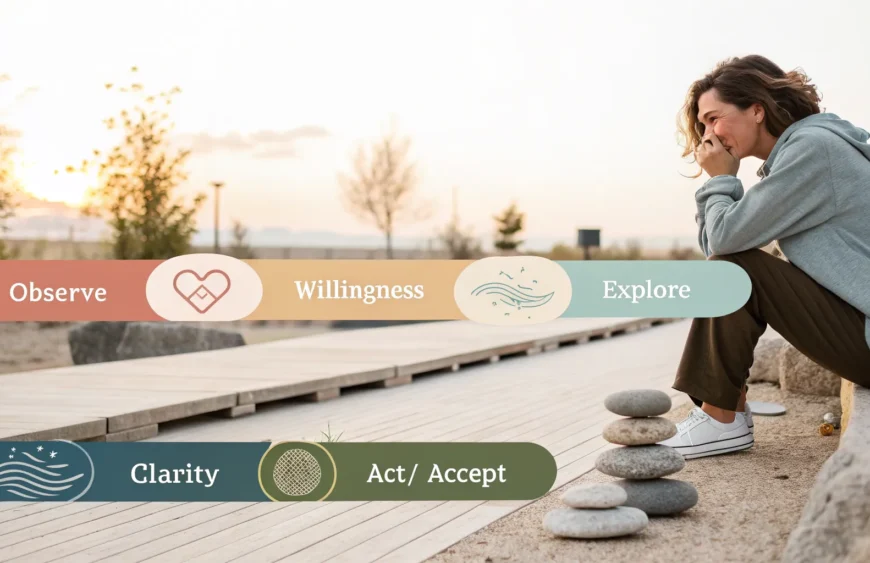

We will structure our guide around five practical steps that form an emotion-processing model. These are:

- Observe — notice what’s happening inside us and around us.

- Willingness — choose to hold the feeling without fighting it.

- Explore — make the experience concrete and investigate the thoughts and rules behind it.

- Clarify (Locus of Control & Values) — decide what is in our control and what matters most.

- Act or Accept — take steps that align with our values, or accept what we cannot change.

We’ll interweave storytelling, clinical reasoning, practical exercises (including simple brain dumps and breathing), and compassionate humor — because sometimes a light-hearted remark is the only place where a weary nervous system can exhale. Ready? Let’s begin with step one.

Step 1: Observe — See what Anxiety really looks like 👀

We begin with the simple but radical act of looking. Observation sounds easy — and then Anxiety turns up the volume and we do everything in our power to mute it. But observation is the first, essential skill: it gives us data. We are not trying to “fix” anything yet; we are gathering information. We ask ourselves: What am I feeling? What is my mind saying? What sensations are in my body?

Picture Jane, who wakes each morning feeling jittery for no clear reason. We could tell her to relax, but that’s like telling the radio to be quieter without touching the dial. Instead we encourage Jane to notice: “I feel jittery. There’s a buzzing behind my ribs. My hands are slightly cold and my jaw feels tight.” Observing like this does three big things: it separates the sensation from meaning, it reduces fusion with panic, and it paradoxically helps the nervous system settle because we stop fighting what’s happening.

We use a handful of practical micro-skills during observation:

- Noticing: “I am feeling something.”

- Naming the emotion with specificity: “I feel apprehensive” rather than “I feel bad.”

- Locating the sensation: “It’s a tightness in the chest” or “butterflies in the stomach.”

- Diffusion: “I’m having the thought that I wish this would go away,” rather than becoming the thought.

- Non-judgmental description: “This is uncomfortable” instead of “This is terrible.”

Consider Bob, who fears social situations. His automatic thoughts might be, “Everyone will judge me,” or “I’ll say something stupid.” During observation we simply write those thoughts down as thoughts: “I’m having the thought that everyone will judge me.” That separation — this cognitive diffusion — is profoundly stabilizing.

One small practice we often use: set a timer for two minutes, find a place to sit, and simply notice. We wiggle the toes, feel the chair beneath us, and say out loud: “I am noticing anxiety in my chest.” That tiny act rolls back the tide of avoidance just enough that the next step — willingness — becomes possible.

Step 2: Willingness — Lean in, don’t run away 🌬️

Willingness is the secret ingredient. If observation is the act of seeing, willingness is choosing to stay present with what we see. Most of us have a reflex to distract: scroll, snack, tidy, avoid. These actions may bring short relief but they keep Anxiety alive and loud. Willingness says: We will allow ourselves to feel without using avoidance or compulsion to escape.

Why is willingness so powerful with Anxiety? Because anxiety’s core message is often “danger.” The body lights the alarm bells. If we always flee, we never teach the alarm that the situation is safe. Willingness lets the alarm run its course long enough for our nervous system to learn. It’s like keeping a bandage on a wound long enough for it to scab. If we peel it off every hour, we never heal.

Here are ways we practice willingness with our three friends:

- Jane (general Anxiety): Instead of doom-scrolling, she sits, closes her eyes, and takes a slow breath. She notices the jitteriness and says, “I can feel this. I can be with this.” Sometimes we suggest exaggerating the sensation — let the hands shake a little — which paradoxically reduces the sense of needing to control it.

- Fred (event Anxiety): Before a big presentation he tends to procrastinate. Willingness for him looks like a phone-free walk, letting the body move, then writing a brain dump: what’s left to prepare, what we’re confident about, what we need feedback on. Willingness doesn’t mean denying preparation; it allows preparation without panic.

- Bob (social Anxiety): Willingness looks like arriving at a small gathering and staying for longer than his instinct says. He acknowledges the discomfort and decides to be present anyway: “Bring it on, anxiety. I can feel anxious and still be here.” This changes the internal rules.

We sometimes teach a quick anchoring technique: slow breath in for four, hold for a second, out for six. Feel the feet, feel the butt in the chair, and say, “I am allowing this.” That short ritual breaks the habitual pattern of escape.

Step 3: Explore — Make Anxiety concrete and interrogate it 🕵️♀️

Now that we’ve observed and chosen willingness, we get curious. Exploration is detective work. Anxiety is like a smoke alarm that screams; our job is to check whether there’s actually a fire or whether we simply burned the toast. We test the signal: is there real danger, or is it an overactive alarm? We ask clarifying questions and make the worry concrete — write it, diagram it, say it aloud.

Exploration is about two interrelated tasks: examining the facts (Is there a real threat?) and examining the thinking patterns that amplify Anxiety (Are we catastrophizing? Engaging in black-and-white thinking? Filtering only the negative?).

Let’s return to Bob: he believes everyone will judge him harshly. We encourage him to test that belief. What evidence supports it? What evidence contradicts it? If everyone did judge him, what would happen? Usually the imagined catastrophe is far worse than what reality actually holds. By writing down the thought and asking factual questions, we reduce the emotional charge around it.

For Jane, exploration often reveals a series of small, unattended stressors adding up. She might list bills, a messy room, lack of sleep, too much caffeine, too many obligations, and never saying no. When we write those items down, Anxiety becomes solvable rather than amorphous. We see patterns: what’s within our control and what’s not, what needs an action plan and what needs acceptance.

For Fred, exploration helps him separate preparation from avoidance. He may notice that his procrastination feels productive (“I’m studying all night!”) but actually undermines performance. A simple table-like list — which we often write as bullet points — clarifies what he needs: rehearsal, structure, feedback, and a plan for the night before.

Exploration also includes examining unwritten rules. Do we believe, “If I’m not perfect, I must withdraw”? Rules like that escalate Anxiety and limit growth. If we name those rules, we can intentionally revise them: “It’s okay not to be perfect. I can still connect even if I fumble a sentence.”

Step 4: Clarify — Locus of Control and Values ⚖️

Clarification is where the rubber meets the road. After exploring, we separate what we can change from what we can’t — the locus of control activity — and we bring values into focus so we know where to put our energy. This step gives us clear options: act, or accept.

Locus of control looks deceptively simple: make two columns — what we control and what we don’t. Fred can’t control his stomach fluttering before a presentation. He can’t control the audience’s reaction. What he can control is preparation, rehearsal, asking for feedback, and showing up. That realization moves him from helplessness to agency.

The values activity helps us prioritize. Suppose we truly value connection. If Anxiety tells us to avoid a party, asking, “Do we value connection more than comfort?” clarifies the choice. Bob might decide that authentic friendships are worth a little discomfort. Jane might decide that being rested and organized matters more than being constantly available to everyone. These clarifications shape our action plans.

We often use a practical exercise: list three life domains (relationships, work/study, health). For each domain, write one value and one action. Example:

- Relationships — Value: Connection — Action: Attend one social event this month.

- Work — Value: Competence — Action: Create a 30-minute daily practice plan for the presentation.

- Health — Value: Well-being — Action: Reduce caffeine after 2 p.m., and schedule one brisk walk daily.

This exercise becomes a compass. When Anxiety arrives and tries to steer in the opposite direction, we check our values list: is avoidance aligned with what we want? If not, we make a smaller, value-aligned step.

Step 5: Act or Accept — Choose the next step and follow through 🚶♀️

This is the moment where we either take a step toward our life or deliberately accept what we cannot change. Both are courageous. Action might be small — organizing a drawer, calling a friend, rehearsing a 5-minute section of a presentation — or big, like going to a party despite fear. Acceptance means we make space for discomfort when change is not possible or helpful.

We find that combining action and acceptance usually works best. Fred can practice his part and accept that his hands might still shake; he prepares and makes room for the physical sensations. Jane can clean her room and contact her brother about budgeting — action — and accept that she may still feel uneasy sometimes — acceptance. Bob can go to one social event and be present while noticing his heart rate; he acts and accepts the discomfort as part of caring for connection.

A practical way to plan action is to pick one small, achievable step that aligns with values, write it down, and schedule it. We keep the step tiny enough that Anxiety doesn’t hijack it. Want to exercise more? Start with a 10-minute walk. Want to reduce work overwhelm? Choose one file to sort today. Little wins accumulate and teach our brains new patterns.

Practical exercises we can use right now 🛠️

We love concrete, simple exercises. They cut through the fog that Anxiety creates and give us immediate leverage. Below are some of the most reliable tools we use clinically and personally:

- Two-minute observation: Sit, feel your feet, notice sensations for two minutes. Name one physical sensation and one thought. Breathe slowly.

- Willingness breath: In for four, out for six. Repeat five times and notice what changes.

- Brain dump: Set a timer for ten minutes and write everything on your mind. Don’t edit. Then circle three actionable items.

- Locus of control list: Make two columns: What we control vs. what we don’t. Put realistic items in each column.

- Values micro-step: Pick one value and one 10-minute action this week that expresses it.

- Exposure with a plan: For social Anxiety, make a graded exposure list and start with a manageable step (e.g., 15-minute conversation with a friendly acquaintance).

We often pair these with movement — a walk without the phone, shaking the body, or light stretching. The body’s movement helps metabolize stress hormones and makes it easier to think clearly.

How Anxiety behaves in different common scenarios — applied examples 🎯

We promised practical examples, so here they are in real detail. We’ll walk through Bob (social Anxiety), Jane (general Anxiety), and Fred (event Anxiety) so that the steps feel alive and applicable.

Bob — Social Anxiety

Bob’s symptoms: worry about being judged, avoidance of parties, overpreparing or staying home, constant self-monitoring. Our approach with Bob follows the five-step process:

- Observe: He notices the tightness in his throat and his thoughts: “Everyone will think I’m awkward.”

- Willingness: He decides to attend a small gathering and stay at least 30 minutes despite discomfort.

- Explore: He writes the thought down and tests it: what evidence exists that everyone will judge him? What alternative explanations exist? He identifies an unwritten rule: “If I’m not perfect, I should withdraw.”

- Clarify: He lists what’s in and out of his control and clarifies values: connection matters more than comfort.

- Act or Accept: He goes to one event, practices an approach script, and accepts the lingering discomfort as part of caring about relationships.

Over time, repeated small exposures teach Bob’s nervous system that being with people isn’t actually a life-threatening event. The alarm quiets.

Jane — General Anxiety

Jane’s symptoms: low-level, chronic jitteriness, constant busyness, avoidance via screens and food, trouble sleeping. For Jane the work is often practical life management combined with emotional processing:

- Observe: She notices a general sense of unease and lists sensations — tight shoulders, restless legs, inability to relax.

- Willingness: She sits quietly for five minutes each day and practices letting the feeling be present.

- Explore: She does a brain dump and writes: bills, messy room, too much caffeine, overscheduling, lack of boundaries. Each item is concrete and actionable.

- Clarify: She decides what she can control (paying bills, saying no) and what she can’t (unexpected medical bills). She clarifies values: family, calm, sustainability.

- Act or Accept: She chooses one small action: clean a corner of the room and set up a budget appointment with her brother. She accepts that Anxiety may persist but that she can take real steps that reduce the burden.

We see dramatic shifts when people like Jane stop trying to only “manage” Anxiety and instead tackle the backlog of small stressors that create a constant hum of dread.

Fred — Event Anxiety (performance, presentation)

Fred’s symptoms: intense worry before an important presentation, procrastination, rehearsal to the point of burnout, sleep difficulty. The process helps him structure preparation and acceptance:

- Observe: He notices a pit in his stomach and thoughts about failing.

- Willingness: He allows the anxiety and chooses to do a short, phone-free walk to shake out excess energy.

- Explore: He does a brain dump: What’s prepared? What’s not? What feedback can he get? Where is catastrophic thinking present?

- Clarify: He lists what he can control (practice, timing, feedback) and what he can’t (exact grade). He clarifies values: doing the best work possible and learning.

- Act or Accept: He rehearses in front of a friend, asks for feedback, and accepts that his hands may shake — it’s part of caring. He shows up anyway.

For Fred, acceptance reduces the performance pressure and improves his ability to think during the event. Preparation plus a willingness to feel the sensations often leads to a better outcome than frantic, avoidant hyper-preparation.

Quick reference "data table" — practical comparisons (presented as a list) 📊

We promised a useful quick reference to compare the different types of Anxiety and what tends to help most. Because we can’t use a formal table here, we present the “table” as clear list rows:

- Social Anxiety (Bob) — Symptoms: fear of judgment, avoidance; Best initial step: graded exposure + willingness to stay a short amount of time; Value focus: connection.

- General Anxiety (Jane) — Symptoms: chronic jitteriness, diffuse worry; Best initial step: brain dump + life management actions (sleep, caffeine, boundaries); Value focus: calm and sustainability.

- Event Anxiety (Fred) — Symptoms: spikes before performance, procrastination; Best initial step: structured rehearsal + brain dump of tasks; Value focus: competence and learning.

- Common threads — Skills that help across types: observation, willingness, diffusion, values clarification, action planning.

Why this works: the brain and body explanation 🧠

If we want Anxiety to change, we have to understand what it’s trying to do. The brain’s alarm systems — ancient and excellent at keeping species alive — can get overprotective. When the alarm signals danger repeatedly when nothing life-threatening is happening, it becomes hypervigilant. Our job is not to fight the alarm but to teach it with experiences: “We survived that party. We survived that presentation.” Over time the alarm reduces its sensitivity.

Two biological truths help us here: first, the nervous system calms after the stress response has been activated and then allowed to complete. Second, avoidance prevents the completion of that cycle. Willingness and exposure allow the nervous system to finish the loop, which reduces baseline anxiety.

We also note that cognitive habits — catastrophizing, mental filtering, black-and-white thinking — amplify the alarm. Clear observation plus exploration helps us reframe those thoughts so the alarm can be recalibrated.

Common obstacles and how we work around them 🧩

In our work, we often see people who try hard at first and then slip back into old patterns. Here are common obstacles and practical ways we navigate them:

- Obstacle: Perfectionism — The rule “if it’s not perfect I’ll withdraw.”

Our workaround: Start with micro-exposures and deliberately practice imperfection. We rehearse saying something minor that’s slightly awkward and notice the world didn’t end. - Obstacle: Overwhelm — Too many things to tackle.

Our workaround: Brain dump and choose one small action. Repeat weekly. Celebrate small wins. - Obstacle: Shame — “I shouldn’t feel this way.”

Our workaround: Normalize the feeling and practice compassionate self-talk. We are not broken for experiencing Anxiety; we are human. - Obstacle: Inconsistent practice — We do great for a week and then forget.

Our workaround: Habit stacking — attach one micro-practice to an existing routine (after brushing teeth, do a two-minute observation).

Tips to make these practices feel natural (and a little humorous) 😄

Practicing these skills doesn’t have to be solemn or grim. We invite a little humor because it lightens the load and helps the nervous system relax. Try these playful hacks:

- Give your Anxiety a silly name for five minutes — “Hello, Sir Jitters.” That small distance makes it less tyrannical.

- Do a dramatic over-the-top shake-out dance for 20 seconds when you feel frozen. It’s silly, it moves energy, and it often dissolves tension.

- Reward micro-exposures. Survived a 15-minute social event? Treat yourself to a single square of chocolate or five minutes of music you love.

- Use humor to create suspense: tell your anxious inner voice, “Wait! Don’t tell me what will happen yet — I’ll be back after coffee.” The cliffhanger gives us breathing room.

Yes, the tension in the stomach is real. But so is our capacity for play. We can use both to change the story.

How we know this works — the learning loop 🔁

The mechanism of change is simple yet profound. We repeatedly face a feared situation (in a graded way), we survive it, and the brain learns safety. Each successful exposure shrinks the perceived threat. The loop is: Observe → Willingness → Explore → Clarify → Act/Accept → Survive → Learn → Repeat.

Our clinical experience and the science behind exposure and acceptance-based therapies show that this learning loop gradually decreases baseline Anxiety and increases confidence. But importantly, even if Anxiety doesn’t disappear entirely, living by our values produces a richer life. Doing what matters matters more than being perfectly comfortable all the time.

❓ FAQ: Questions are often heard (and honest answers)

Q1: Q: Will Anxiety ever completely go away?

We don’t usually expect Anxiety to vanish forever, and that’s okay. Anxiety is a sign that we care about something — our relationships, our work, our safety. The goal isn’t annihilation; it’s learning to live a meaningful life even when Anxiety visits. With consistent practice, frequency and intensity usually lessen, and our capacity to handle it grows.

Q2: What if I try these steps and my Anxiety gets worse?

Sometimes Anxiety increases initially when we begin to face it — that’s normal. The early phase of exposure or willingness can spike discomfort. We recommend pacing: choose micro-steps and pair them with grounding practices. If Anxiety becomes overwhelming or if there’s a risk of harm, seek professional support. We can grow tolerances gradually and safely.

Q3: Q: How often should we practice these skills?

Daily micro-practices are most effective. Two minutes of observation, a five-minute brain dump, or a short willingness breathing practice each day builds tolerance. The key is consistency, not duration. Small repeated exposures recalibrate the nervous system.

Q4: What if my Anxiety is caused by trauma?

Trauma-related Anxiety can be more complex and often benefits from trauma-informed therapies (EMDR, somatic experiencing, etc.) and professional guidance. The same core steps — notice, willingness, explore, clarify, act or accept — remain useful, but we proceed with additional care and support.

Q5: Can medication help?

Medication can be an important part of treatment for many people, especially when Anxiety is severe. Medication can reduce symptoms so that therapy and self-help skills become more accessible. Medication decisions should be made with a medical professional.

When to seek professional help — red flags 🚨

We encourage everyone to try these steps, but sometimes we need extra support. Seek professional help if:

- Our Anxiety is so severe it prevents basic functioning (work, relationships, self-care).

- We have thoughts of harming ourselves or others.

- There’s comorbid depression, substance misuse, or trauma that makes self-guided work unsafe.

- We’ve tried these strategies consistently and symptoms are worsening or not improving.

When in crisis, call emergency services or a crisis hotline. You don’t have to do this alone.

A cliffhanger — an invitation to keep exploring... ⏳

We’ve given a full roadmap, yet we’ll leave one question dangling to spark curiosity: what happens next when we combine small daily practices with a deep values-based life? The answer is both simple and ongoing — we get better. We build a nervous system that tolerates discomfort while still moving intentionally toward what matters. If that feels like a sentence with a thousand commas and a suspenseful pause at the end, that’s because it is. The journey keeps unfolding.

We could go on — trauma-sensitive variations, family systems, polyvagal exercises, and more — but for now we’ll close the loop in a way that invites you to practice the first small step. We promise: if you observe, be willing, and take one tiny action, the story begins to change.

Final thoughts — encouragement and a call to action 🌱

We want to leave you with three clear, doable invitations. Pick one and do it today:

- Observe for two minutes: notice one physical sensation and one thought.

- Do a five-minute brain dump and circle three actionable items — choose one and schedule it.

- Make a values list with one micro-step that expresses a value; commit to that step within the next 48 hours.

If you do one of those things today, you have begun the process of changing your relationship with Anxiety. Remember, Anxiety is a sign that we care — and caring is not a defect; it’s the most human part of us. We don’t want Anxiety to disappear entirely because it motivates us to create safety and meaning. We simply want to learn how to carry it more skillfully so it doesn’t control whether we show up for the life we want.

If you’d like structured practice, we’ve developed a workbook and course that walks through the skills in depth — if you’re curious, consider exploring resources that provide guided exercises and community support. Whatever you choose, keep practicing, be gentle with yourself, and remember: small steps taken repeatedly lead to big change.

If you’d like structured practice, we’ve developed a workbook and course that walks through the skills in depth — if you’re curious, consider exploring resources that provide guided exercises and community support. Whatever you choose, keep practicing, be gentle with yourself, and remember: small steps taken repeatedly lead to big change.

Call to action: Today, observe for two minutes, pick one small action aligned with your values, and take it. If you found this guide helpful, we encourage you to share it with someone who might need it — sometimes one tiny nudge changes a whole day.

Great Choices

Resources

Anxiety disorders World Health Organization (WHO)

Childhood-Onset Fluency Disorder: Perspectives on Comorbid Anxiety and Stuttering Psychiatric Times

Navigating the anxiety of change while notching the improvements AADC News

Anxiety in Hypothyroidism: High Prevalence and Significant Treatment Response in a Rural Nepalese Cohort Cureus

John Candy Dealt with ‘Crippling Chronic Anxiety,’ Went to Therapy to ‘Understand What Was Happening to Him’ People.com

Students can manage anxiety through program that helps them imagine positive outcomes Medical Xpress

How to help kids with back-to-school anxiety The Seattle Times

I Think This Will Fix Me: Are We Going Too Far In Our Quest For Wellness? Harper’s Bazaar Arabia

What doctors wish patients knew about managing anxiety disorders American Medical Association

Note: FriscoStore.com may get a small commission from this article, which supports us in giving the scope of great sellers and products and keeping you safe online when you shop for unique, quality items.